How to Motivate Employees Effectively?

For decades, motivating people at work has been a central topic in management science, organizational psychology, and labor studies. Yet in many organizations, motivation is still reduced to quarterly bonuses, a gym membership, and the occasional “good job.” In reality, employee motivation is one of the most powerful drivers of performance, team stability, and long-term organizational growth. Without it, there is no sustained innovation, no accountability, and no real employee engagement.

If you truly want to understand how to motivate employees, you need a broader lens—one grounded in research, motivation theory, labor market realities, and everyday leadership practice. This applies equally to office-based roles and operational or production jobs. Motivation is not a perk; it is a core mechanism shaping how employees show up, perform, and commit their best effort.

Understanding Employee Motivation

From a psychological perspective, employee motivation refers to a set of internal and external processes that activate behavior, shape how work is performed, and determine persistence in pursuing goals. It is not a personality trait and not something employees simply “have or lack.” Motivation emerges from the interaction between the person, the job, and the work environment.

A critical distinction in motivation research is between:

- Intrinsic motivation, driven by meaning, autonomy, competence, and growth

- Extrinsic motivation, driven by rewards, penalties, performance bonuses, and other financial incentives

Decades of research by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan (Self-Determination Theory) demonstrate that organizations achieve the strongest long-term outcomes when they integrate extrinsic motivation with conditions that support intrinsic motivation. Money and control may boost short-term output, but they do not foster ownership, commitment, or employee satisfaction. When work becomes just a paycheck, motivation erodes quickly.

Why Motivating Employees Is Harder Than Ever

Not long ago, the psychological contract between employer and employee was relatively simple. Employers offered stability and pay; employees offered loyalty and execution. That contract has largely disappeared—not because employees have changed, but because the nature of work itself has changed.

The pandemic was a catalyst, not the root cause. It exposed a hidden truth: many motivation systems relied on habit, supervision, and structure rather than genuine meaning. When offices closed and direct oversight disappeared, many employees began asking questions they had long suppressed: Why am I doing this? Does this job matter? What do I gain beyond paying rent?

From the standpoint of work psychology, this was a turning point. Today, many employees no longer define work motivation solely through compensation. While pay remains a basic need, it is no longer sufficient. Employees crave autonomy, alignment with values, and influence over their own work. They want more agency in how tasks are done, how time is structured, and how decisions are made. A lack of autonomy is now one of the strongest predictors of disengagement, particularly in knowledge-based roles.

Time, Energy, and Motivation at Work

Equally important is how employees think about time and energy. Flexible work schedules are no longer a perk—they are a protective mechanism. In a world of constant digital availability, maintaining a healthy work life balance is essential for well being and sustainable employee performance.

Research consistently shows that motivation built on pressure, chronic overtime, and “always-on” cultures leads to burnout, declining morale, and higher turnover. Rather than driving high performance, such environments accelerate employee exit. Engaged employees are not those who sacrifice everything, but those who can sustain focus and energy over time.

Psychological safety plays a crucial role here. Employees who feel safe to speak up, admit mistakes, and seek guidance are far more likely to take responsibility and contribute innovative solutions. Where psychological safety is absent, motivation collapses into survival mode—employees do the minimum, avoid risk, and withdraw mentally, even if they remain physically present.

Growth, Learning, and the Future of Motivation

Another critical dimension of modern motivation is growth. In an economy where skills become obsolete quickly, motivation is increasingly tied to future employability. Employees want career growth, not merely a place on the corporate ladder. They seek professional development, further education, and opportunities to build new skills—even if they currently have only a few skills relevant to the role.

A lack of growth opportunities is now one of the strongest drivers of declining morale and disengagement, even in well-paid jobs. Employees feel valued when organizations invest in employee development, continuous learning, and long-term capability building. This is where recognition programs, meaningful feedback, and clear development pathways have a tremendous impact on employee retention.

A New Reality for Leaders

As a result, motivating employees today is harder precisely because it is no longer simple. There is no single formula, no universal set of perks, no incentive plan that works for everyone. Effective motivation now requires a deeper understanding of human behavior, job design, and organizational systems.

For many managers, this shift is challenging—but it also represents an opportunity. Organizations that treat motivation as something to design, rather than a problem to fix, create a supportive environment where employees feel valued, take ownership of their own decisions, and align their effort with company goals. When done well, motivation becomes a vital factor in long-term organization’s success, not a recurring crisis to manage.

Motivational Techniques — Where They Come From and Why They Still Work (or Don’t)

To understand modern ways to motivate and effective methods to motivate employees, it is worth returning to the scientific roots of motivation theory and tracing how managerial thinking has evolved over time. The earliest motivational techniques in management emerged at the turn of the 20th century and were strongly shaped by behaviorism. Frederick Taylor and the school of scientific management assumed that people respond primarily to external stimuli and that work motivation for high performance stems from a simple cost–benefit calculation. In this model, financial incentives, productivity norms, and tight control dominated.

This approach proved effective for simple, repetitive tasks, but its limitations quickly became evident—especially in roles where the actual work involves thinking, judgment, and accountability rather than mechanical execution. When work requires initiative and decision-making, motivation based solely on external rewards produces compliance, not commitment.

A major shift came with humanistic psychology and research on human needs at work. Thinkers such as Abraham Maslow and later Frederick Herzberg demonstrated that employee motivation works only when organizations address needs that go beyond compensation. Herzberg famously distinguished between hygiene factors (pay, conditions) and true motivators such as responsibility, recognition, meaning, and career growth. This marked a turning point: organizations began to understand that employees seek more than economic security—they seek impact, mastery, and growth.

In the second half of the 20th century, motivation research increasingly emphasized autonomy and relationships. Participative management concepts—revolutionary at the time—introduced practices such as listening to their opinions, involving people in decision-making, and treating employees as partners rather than resources. From a work psychology perspective, these practices drive team motivation because they activate intrinsic motivation and a strong sense of agency. When employees feel trusted to make own decisions, they invest more of their best effort.

Modern ways to motivate employees draw on this entire body of research, but in far more nuanced ways. Effective organizations understand that no single technique works universally. Thoughtfully designed methods to motivate employees balance stability and basic needs with aspirations for personal development and purpose. Employees increasingly expect work to provide meaning, learning, and alignment with values—not merely income. This is why many leaders now focus on job design and employee autonomy, rather than relying solely on reward systems.

From a business perspective, this leads to a critical insight: motivational techniques are not tricks to deploy once and forget. They are psychologically informed tools that work only when adapted to people, context, and organizational maturity. When organizations recognize employees’ needs, support growth, and encourage ownership, motivation ceases to be a recurring problem and becomes a self-regulating force within the work environment.

Key Drivers of Employee Engagement — What Actually Works

A wide range of global studies—including research synthesized by Gallup, Harvard Business Review, the OECD, and the Boston Consulting Group—shows that the important factors driving employee engagement are remarkably consistent across industries and cultures. What varies is not what motivates people, but which factors dominate at different stages of a career or in different roles.

One of the most powerful and consistently validated drivers is a sense of meaning. Employees who understand how their daily actions connect to company goals and the broader company’s mission show higher employee satisfaction, resilience, and initiative. From a psychological standpoint, meaning activates intrinsic regulation—employees work not because they must, but because the work has a positive impact. When meaning is absent, many employees disengage emotionally, leading to the phenomenon known as quiet quitting—a pattern widely discussed in HR and labor research.

Equally critical is security, understood not only as job stability but as psychological safety. Research consistently shows that when expectations are clear, decision-making is transparent, and people can speak openly without fear, employees feel safe to take responsibility. In contrast, unsafe environments push people toward risk avoidance and minimal effort, undermining employee performance and continuous improvement.

A third foundational pillar is relationships. Gallup’s research repeatedly confirms that strong relationships—with managers and co workers—are among the strongest predictors of engagement. When employees feel valued, respected, and connected, motivation deepens far more than through isolated rewards. These strong relationships satisfy essential social factors, without which even well-designed recognition programs and performance bonuses lose effectiveness.

Taken together, the evidence leads to a clear conclusion: sustainable motivation does not come from piling on incentives. It comes from designing a supportive environment that fosters meaning, safety, and connection. These elements—not isolated perks—create engaged employees, better employee retention, and ultimately drive the organization’s success.

Motivating Office Employees — Autonomy, Meaning, and Growth

For office-based roles, motivation is increasingly disconnected from compensation alone. A growing body of research shows that long-term employee engagement depends far more on autonomy and opportunities for growth than on pay increases. While compensation remains a baseline expectation, it rarely sustains motivation on its own.

Flexible work schedules, hybrid models, and autonomy over time management allow employees to better integrate their job with their personal lives, supporting a healthy work life balance. This balance directly affects focus, cognitive capacity, and overall employee performance. When employees feel trusted to manage their own time and priorities, they tend to invest more energy in their own work and demonstrate higher levels of accountability.

Equally important is feedback quality. Constructive feedback and positive feedback, delivered regularly and grounded in observable behaviors, reinforce competence and direction. Office employees want to understand how their work is evaluated and how it contributes to broader outcomes. When feedback supports learning rather than control, it accelerates employee growth, strengthens motivation, and supports long-term career growth beyond simply climbing the corporate ladder.

Motivating Frontline and Production Employees — Stability and Fairness

Motivating frontline and production employees requires a different emphasis, but no less psychological awareness. In these roles, clarity and fairness are essential. Clear expectations, visible standards, and safety in the work environment are foundational to motivation.

Here, financial incentives such as performance bonuses tied to measurable outcomes play a meaningful role. However, research consistently shows that even in operational settings, motivation declines sharply when employees experience disrespect, inconsistent rules, or organizational chaos. In such conditions, employees feel disconnected and disengaged, regardless of pay.

Stabilizing benefits—such as predictable schedules, healthcare coverage, and job security—support employee morale and reinforce trust. When employees feel protected and treated fairly, they are more willing to take responsibility and contribute to company goals, rather than merely completing tasks.

Financial and Non-Financial Motivation — Finding the Right Balance

Financial rewards remain an important component of motivation, but their effectiveness depends entirely on design. Incentives must be clear, achievable, and transparently linked to results. When rewards are perceived as arbitrary, they erode trust instead of reinforcing performance.

At the same time, non-financial drivers play an increasingly central role. Professional development, learning opportunities, team-building experiences, and autonomy in decision-making strengthen intrinsic motivation. These elements encourage employees to invest discretionary effort and support continuous learning and continuous improvement.

Leading organizations no longer treat these factors as optional perks. They embed them into the core of how work is designed and managed, recognizing their tremendous impact on motivation and retention.

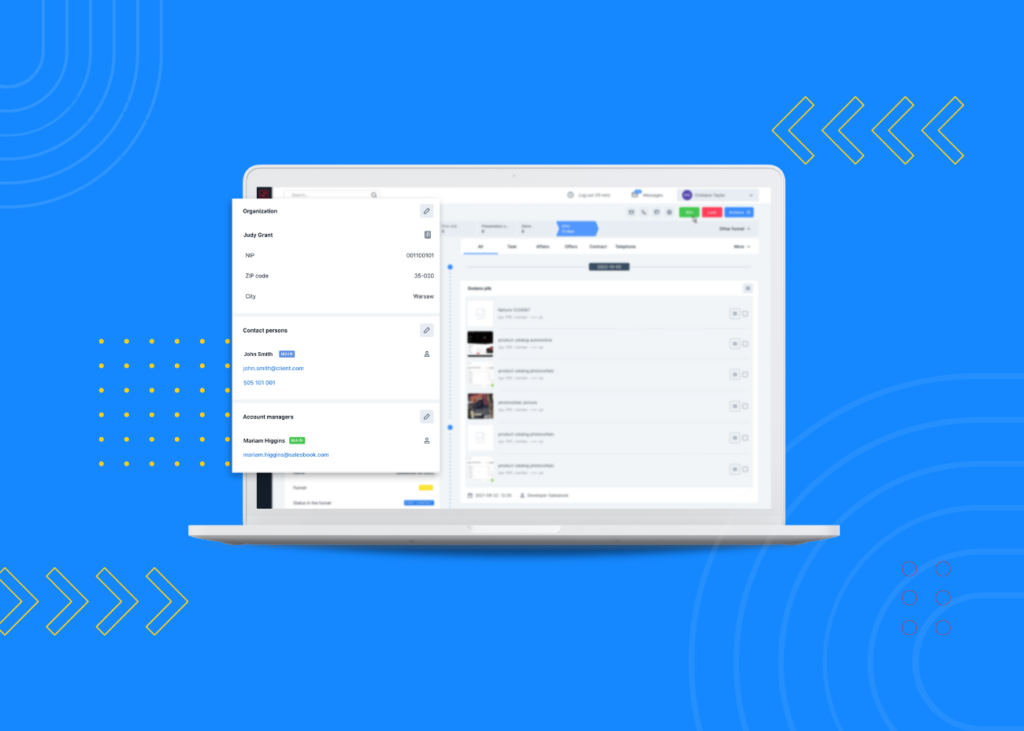

The Motivation System as a Strategic Tool

A well-designed motivation system is not an HR add-on—it is a strategic framework that shapes behavior across the organization. Effective systems recognize differences between roles, respect individual needs, and balance structure with autonomy.

They rely on clear communication, consistent evaluation criteria, and ongoing dialogue rather than annual reviews alone. Systems that ignore individual differences or rely purely on managerial discretion undermine trust. In contrast, systems that align motivation with values and objectives create positive outcomes for both employees and the organization.

Motivation and Performance — A Proven Relationship

There is little debate in the research: motivation and performance are tightly linked. Gallup’s studies consistently show that teams with high engagement deliver better results, experience lower turnover, and demonstrate stronger quality outcomes.

Motivated employees are more resilient under pressure, take ownership of outcomes, and align their efforts with the organization’s success. They do not simply complete tasks; they contribute to problem-solving, innovation, and long-term value creation.

From a leadership perspective, investing in motivation is not a cost—it is one of the most effective ways to sustain high performance.

Final Thoughts: How to Motivate Employees in Practice

To motivate your employees effectively is not about pushing harder or relying on short-term pressure. It is about designing conditions in which motivation can emerge and sustain itself over time. Research consistently shows that most employees are willing to give their best effort when work provides meaning, autonomy, and opportunities for growth. When organizations focus solely on external motivators—such as bonuses or promotions—they may influence behavior temporarily, but they rarely shape long-term commitment or resilience.

True motivation develops when leaders intentionally align systems with human needs. Giving employees room to make decisions, face new challenges, and take ownership of outcomes strengthens responsibility and engagement. Equally important is recognizing effort and contribution. Leaders who regularly express gratitude—not as a formality, but as a genuine acknowledgment of value—reinforce the behaviors that organizations want to see repeated. This is how desired behaviors are shaped: not through control, but through reinforcement and meaning.

At the same time, motivation does not exist in isolation. Other factors, such as workload design, team dynamics, and the broader work environment, either amplify or weaken even the best motivational initiatives. This is where effective leadership becomes decisive. Great leaders understand that motivation is not something they impose; it is something they cultivate by modeling values, setting clear expectations, and creating psychological safety.

When leaders combine structure with trust, purpose with autonomy, and recognition with challenge, employees do more than comply—they engage. They adapt, learn, and contribute beyond formal requirements. In such environments, motivation becomes a strategic asset, driving performance, innovation, and long-term organizational success rather than a recurring problem to be fixed.

Table of Contents